November 05, 2025

What data reveals about Meta and Google’s political ad ban in the EU

When Meta and Google announced they would ban political advertising in the European Union ahead of the implementation of the Transparency and Targeting of Political Advertising (TTPA) regulation, the response from digital democracy researchers and civil society was swift and critical. Especially Google’s deletion of 7 years of European political ad history was a blow to transparency.

But beyond the immediate outcry, what does the empirical evidence tell us about the consequences of this decision? And who is more likely to be affected? After 5 years of tracking political advertising across countries all over the world, I can say with confidence that this decision is an outcome that will make elections less transparent and more vulnerable to hidden influence.

The transparency we're gaining(?)

The European regulation that triggered this exodus actually mandates extensive transparency. Under the TTPA, which came into force on October 10, ad providers (entities publishing political ads), ad publishers (platforms distributing them), and sponsoring entities (those financing campaigns) are required to disclose detailed information about their campaigns: targeting methods, data sources used, spending amounts, distribution channels, and the parameters of their audience selection.

Crucially, these disclosures are meant to be publicly accessible through a centralized European repository for online political advertisements, which the European Commission plans to establish by the earliest date of April 10, 2026. The repository is expected to include all online political advertisements published in or directed to EU countries. It will establish a common data structure with standardized metadata, authentication protocols, and an API to enable data aggregation. Each online political ad must remain available in the repository while it is shown and for seven years after it was last shown. This means we face a minimum six-month gap, from October 2025 when Meta exited the political ad market until at least April 2026 when the repository could become operational, during which systematic transparency about political advertising in Europe has effectively disappeared and completely relies on self-reports, for which I do not have high hopes.

Case in point: my initial analysis of self-reporting under the TTPA requirements during the recent Dutch election reveals concerning patterns. The data submitted to platforms like politiekereclame.nl,the centralized Dutch transparency portal launched by media industry associations, is completely unstandardized across advertisers and missing crucial information. Out of 65 campaigns I tracked, only 43 (66%) even report which media channels they used. The three largest campaigns without channel information represent over €3.2 million in spending, including D66's €2.4 million campaign, the biggest spender in the election and likely winner of the election.

More concerning still: the self-reported data lacks the granular targeting information that the TTPA supposedly requires. What exact texts, images, or videos were used to transmit messages? Which data sources were used? What parameters defined the target audience? How were sensitive categories avoided or proxied? These questions, the very ones the regulation was designed to answer, remain unanswered in the vast majority of disclosures.

Until the European repository becomes fully operational and proves effective, researchers are left with a significant transparency gap. We've moved from a flawed but functional system that could be analyzed, studied, and improved to one that exists, for now, primarily on paper. The platforms provided flawed transparency; the self-reporting system, at least so far, provides even less, just a bureaucratic checkbox that allows advertisers to claim compliance while revealing little about how they're actually influencing voters.

The success of the TTPA will ultimately depend on whether the European repository can deliver what the platforms will not: comprehensive, standardized, accessible data about political advertising. If it succeeds, it could represent a genuine improvement over the platform-dependent system we're losing. If it fails, or if enforcement remains weak, we may find ourselves worse off than before, having lost historical data and functional (if imperfect) tools without gaining a workable alternative.

Where will political money flow now?

One question that keeps popping up after the ad ban is: where will the money go now? Because banning political advertising on social media platforms will not end paid political influence on these platforms. It shifts into less transparent channels: influencer campaigns with undisclosed payments, PR firms operating in regulatory grey zones, where the money trail becomes impossible to follow. And perhaps many political ads will simply remain on social media platforms anyway. Past research by AI Forensics and NYU has shown that Meta has been pretty bad at detecting and enforcing its political ad policies. If Meta struggles to enforce its own ad policies when it was trying to label political ads, what makes anyone think a ban will be effectively enforced? Indeed, there are first reports that the political ad ban is not really being executed all that well.

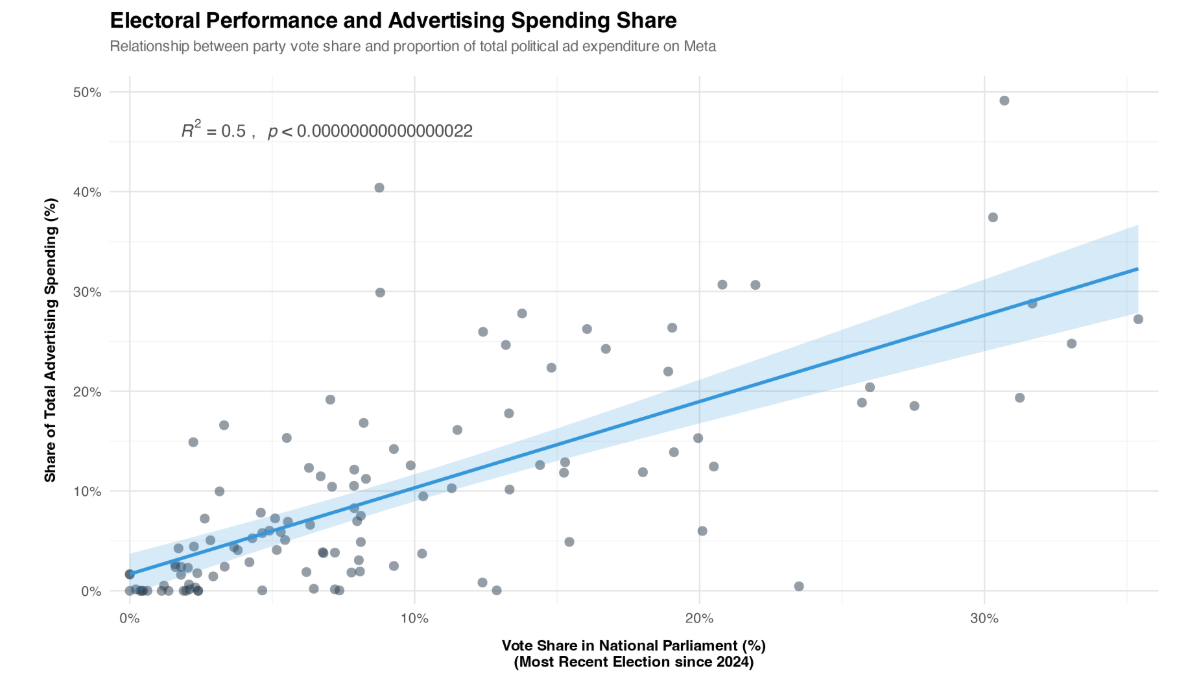

But let us assume the political ad ban is enforced properly after some initial hiccups. The more optimistic view is that banning digital ads levels the playing field, reducing the advantage of well-funded parties. There is some evidence in favor of that: the graph below, compiled with data from Who Targets Me, shows a clear correlation between advertising spending share and vote share, that is, parties that spend more on ads tend to be more successful. This is not because advertising is so powerful; in fact, research finds relatively small effects of political advertising, but larger parties simply have more resources at their disposal to spend on digital advertising.

Note: Each point represents a political party. Line shows linear regression with 95% confidence interval. Pearson correlation coefficient with two-tailed significance test. Election results are part of the Chapel Hill Election Survey. Spending Source: Meta Ad Library Report shows all of the spending since January 2022. Annotations of party accounts from Who Targets Me (whotargets.me).

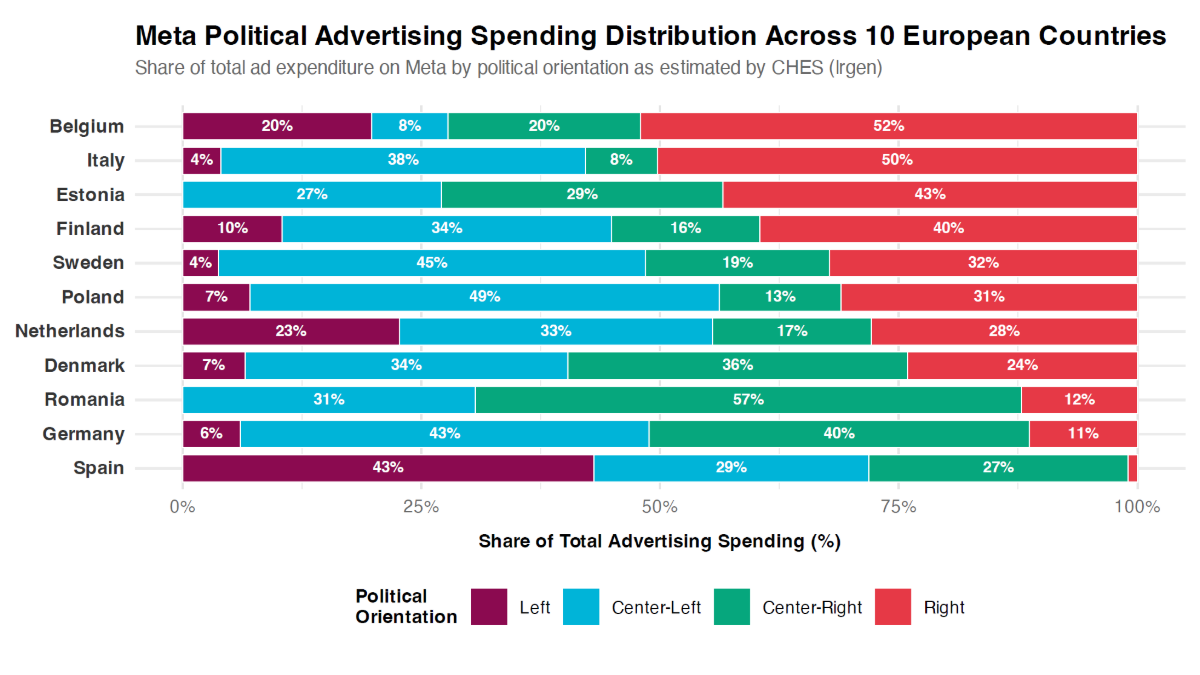

And who are these big spenders? Across the European countries I studied, it is overwhelmingly centrist parties. The graph below shows the distribution of political advertising spending by political orientation across ten countries in the EU. In eight out of ten countries, center-left and center-right parties combined account for half or more of all digital political ad spending on Meta. In some cases, like Germany and Denmark, centrist parties account for 70% or more of total spending.

Note: Political orientation based on party positions on 10 points left-right scale from CHES (<2.5=left, 2.5 to 5=center-left, 5 to 7.5=center-right, >7.5=right). Spending Source: Meta Ad Library Report shows all of the spending since January 2022. Annotations of party accounts from Who Targets Me (whotargets.me).

This creates an interesting dynamic: the optimistic view would suggest that the big, well-funded centrist parties would suffer most from an ad ban, potentially creating more space for smaller parties to compete. But here's the problem with celebrating the death of one inequality: it doesn't spell the end of all other forms of inequality. The unequal playing field of political communication did not start with social media ads and won't end with their ban. There's still TV, radio, print media, billboards, all the traditional channels where some parties and candidates get disproportionate attention. Some politicians are simply better at attracting media coverage, either because they're more charismatic, more controversial, or because they already hold power and are well-funded. The playing field was never level, and banning one form of advertising doesn't level it.

In fact, removing paid political advertising on social media might just hand even more power to the algorithm and those who know how to game it. Research shows that more negative and polarizing content drives higher engagement and gets amplified by platform algorithms. When paid advertising is gone, algorithmic distribution becomes the game in town. And who wins that game? Whoever is most willing to polarize, to emotionalize, to provoke. During our research for the Dutch elections, we tracked a far-right meme page that used AI to generate racist propaganda images and attacks on politicians. Investigative journalists at De Groene Amsterdammer discovered it was run by two far-right members of parliament. In our research, we find that they became the political Facebook page with the most total engagement, even surpassing all other national politicians, until the scandal forced them to delete it. Those MPs understood something crucial: platforms reward emotional intensity over substantive policy discussion. The ad ban arguably makes these dynamics worse by removing one of the few channels where there's at least some transparency about who's paying for what. This is the future the ad ban creates: political influence that's harder to trace, harder to regulate, and easier to hide.

There is also an idea that parties may engage more in outreach on the streets and door-to-door campaigning, perhaps they will "touch grass" more. That is unlikely to happen. Social media advertising was easy and low-hurdle. You had the data from the platforms, you just needed an image or video, a text, and they would handle all the distribution to selected audiences you like and you could reach hundreds of thousands relatively quickly. No need for volunteers, printing costs, or actually talking to people. Now, would resources be freed up to do more out-in-the-streets campaigning? Yes. But are they likely to do it? I think, given the resources, volunteers, and infrastructure needed, it is not a 1-to-1 replacement and requires much more ambition to pull off.

The microtargeting paradox

One argument in favor of the ban suggests it prevents harmful microtargeting practices. But after analyzing targeting strategies across the world in over 113 elections, I can say: this is using a sledgehammer where a scalpel was needed.

Our comparative work on political microtargeting reveals that targeting on Meta platforms is widespread but not as sophisticated or even as micro as many assume. The median election budget spent on ads with three or more targeting criteria is just 7.06%. The most common approach is using a single criterion, typically location. Not any of the more sophisticated targeting methods, such as custom audiences that rely on third-party data (which would enable Cambridge Analytica-style targeting by matching, for example, psychological data).

The sophisticated microtargeting that regulators fear (combining dozens of data points to identify and manipulate narrow voter segments) is relatively rare in practice. Moreover, targeting is not inherently antidemocratic. Through my research, I've observed how niche and issue parties representing pensioners, animal rights advocates, and regional movements use targeting to effectively reach their constituents and mobilize them to vote. You can also think about your local mayoral candidate trying to reach only the city in which she can be elected. In this way, the ad ban doesn't just affect major mainstream parties, it also harms smaller parties and lesser-known local candidates trying to reach specific communities or simply their constituents.

A disastrous failure

In my opinion, the self-imposed political ad ban is a complete failure of platform responsibility that will make our elections less transparent, less fair, and more vulnerable to the whims of algorithms.

The platforms will barely lose any revenue. They'll continue profiting from the engagement that outrageous political content can bring while bearing very little of the responsibility. And voters won't be better informed. They'll be more exposed to algorithmically recommended content during elections, without the checks transparency provides —at the very least, not until the European Ad Library rolls around.

As someone who has dedicated years to mapping and understanding political advertising worldwide, I can see what we're losing. We should call this self-imposed political ad ban what it is: a disaster. And demand better.

This article originally appeared on the Tech Policy Press on 3 November 2025. Find it here.

© Image: Unsplash/Vector elements

More results /

Je medisch dossier inladen in nieuwe functie ChatGPT? Denk 10.000 keer na

Je medisch dossier inladen in nieuwe functie ChatGPT? Denk 10.000 keer na

By Natali Helberger • January 19, 2026

By Roel Dobbe • November 24, 2025

By Roel Dobbe • November 12, 2025

Combatting financial crime with AI at the crossroads of the revised EU AML/CFT regime and the AI Act

Combatting financial crime with AI at the crossroads of the revised EU AML/CFT regime and the AI Act

By Magdalena Brewczyńska • January 16, 2026

By Sabrina Kutscher • July 02, 2025

By Natali Helberger • March 06, 2025

By Maurits Kaptein • June 06, 2025

By Leonie Westerbeek • November 22, 2024

Clouded Judgments: Problematizing Cloud Infrastructures for News Media Companies

Clouded Judgments: Problematizing Cloud Infrastructures for News Media Companies

By Agustin Ferrari Braun • January 29, 2026

By Fabio Votta • November 05, 2025

By Ernesto de León • Fabio Votta • Theo Araujo • Claes de Vreese • October 28, 2025