November 23, 2023

‘Safety Washing’ at the AI Safety Summit

Earlier this month (November 1-2, 2023), tech companies and world leaders gathered at Bletchley Park in the UK to discuss the governance of artificial intelligence (AI), personally hosted by British prime minister Rishi Sunak. In an effort to understand what governments should do to safeguard a future with rapidly evolving AI capabilities, Sunak interviewed tech mogul Elon Musk. For safety engineers, that was an alarm bell, since Musk has an abysmal safety track record, evidenced by ignoring regulatory standards as well as the advice of his safety engineers, both at Tesla and Twitter, with fatal consequences.

With the summit, and all the legitimacy that world leaders have lent to it, the AI policy discussion has taken a wrong turn, looking increasingly like an effort of ‘safety washing’. The faulty and dangerous assumptions behind the AI 'frontier model' agenda, adopted by Sunak and to lesser extent Biden, need to be exposed. More importantly, a more democratic agenda, grounded in material harm and safety analysis, broad stakeholder empowerment, and firm regulatory limits, is urgently needed.

Both existing and emerging risks and harms go unchecked

Recently, Politico reporters showed how both the Biden and Sunak administrations have been infiltrated by AI policy fellows that help foster an agenda focusing on existential risks from increasingly capable AI systems. These fellows are backed by billionaires, of which most ascribe to the effective altruism movement, until recently including crypto criminal Sam Bankman-Fried.

Many have pointed out the issue with focusing on risks of technologies that lie in the future and have not materialized yet, and which lean on problematic assumptions of superintelligence, scenarios for which only science fiction books provide any proof of existence. It draws attention away from well-studied and documented harms and human right violations inflicted with AI systems.

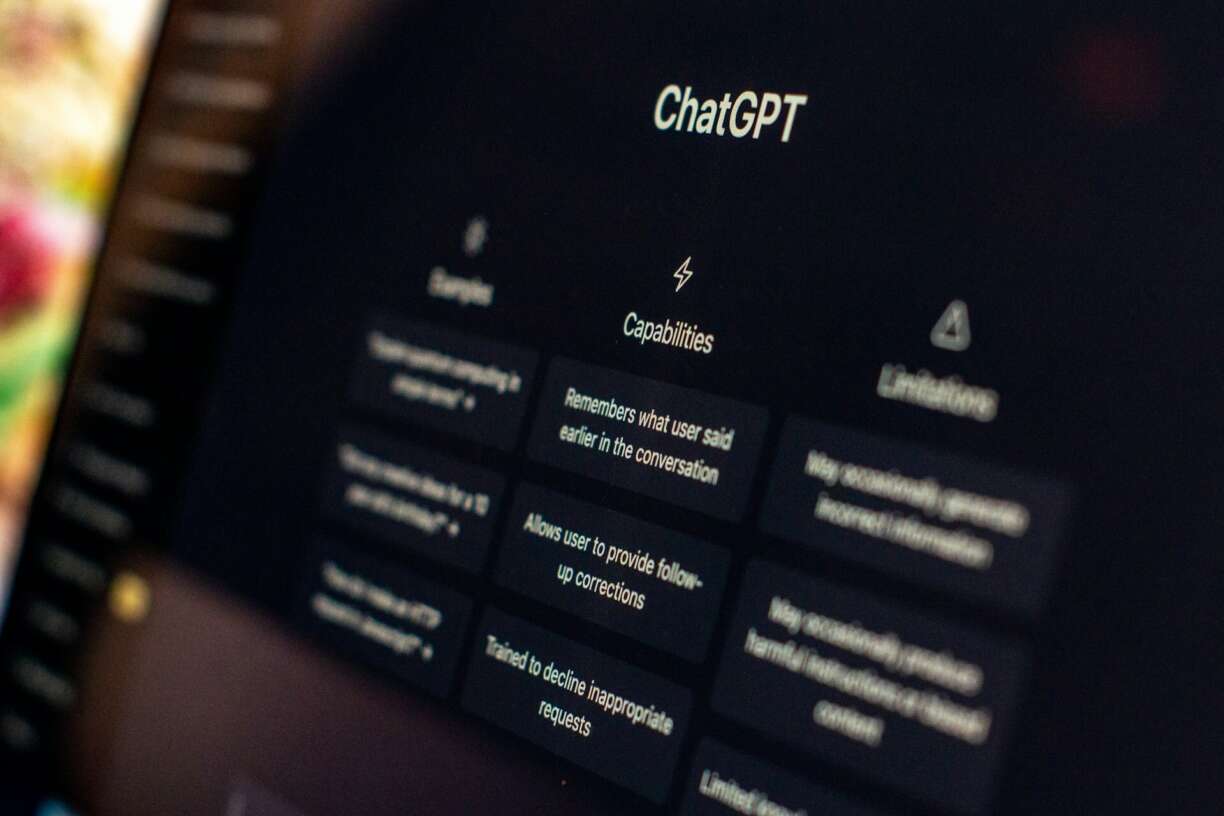

What is less discussed is that the AI safety approaches touted to possibly prevent such existential risks, and which are mostly developed in-house at tech companies, have little to do with actual safety engineering. OpenAI’s ‘super alignment team’ is run by computer scientists whose techniques to ‘learn from human feedback’ focus on the AI model, to produce more acceptable and reliable output. But the history of safety engineering teaches us that more reliable software is not necessarily safer.

“A ‘safe frontier model’ is an oxymoron. Put differently, frontier models are unsafe-by-design and should be treated as such.” — Dr Roel Dobbe, Delft University of Technology

Safe frontier model is an oxymoron

The techno-centric AI safety methods are focused on ‘programming safety into AI models and software’. These will not suffice, and merely offer a safety veneer that cannot compensate for the inherent flaws of “frontier models” used in a plethora of applications and practices, which only lead to harms through how such models interact with humans, other technical systems, and the broader environment. The term ‘frontier model’ has gained traction recently, referring to “highly capable foundation model that could exhibit dangerous capabilities, [including] significant physical harm or the disruption of key societal functions on a global scale“ (https://arxiv.org/abs/2307.03718). But the actual inherent safety risks emerging from more complex models have nothing to do with “capabilities” or “intelligence”, nor with the ability to ‘outsmart’ human beings and the associated existential risk scenarios.

To the contrary, it has been long known that software becomes unsafe when it gets too complex and there is nobody who’se able to sign off for its quality, because no-one understands what it should and should not do. Such baked-in risks of frontier models are thus commonly known as an expression of the ‘curse of flexibility’. For large language models currently championed by the tech industry, such risks are inherent to their design. The curse only gets worse when those building new products and applications on top of such models are not allowed to peek behind the corporate walls that shield the software. Hence, a ‘safe frontier model’ is an oxymoron. Put differently, frontier models are unsafe-by-design and should be treated as such.

Certification is an ineffective and dangerous policy route

Knowing this simple fact, it should become clear that certification or licensing for frontier models will never be able to resolve safety issues related to this curse. If anything, such policy approaches will only further consolidate the ability of tech companies to shield their products in secrecy, with no incentive to worry about the actual safety risks of their flawed models, which typically emerge in the context of use. This monopoly power is hence a huge safety risk in itself.

The lack of respect for basic safety standards and corporate greed remind of the 2008 peanut scandal. Peanuts, produced by Peanut Corporation of America, were exposed to salmonella despite the presence of a certification system. When the company started to have positive tests for salmonella, CEO Stewart Parnell ordered his personnel to retest the peanuts until a negative result was achieved. They also reused prior negative tests to mask positive test results. In 2015, Parnell was sentenced to 28 years in prison for selling food that made people sick and led to nine deaths due to salmonella poisoning.

It is not hyperbolic to draw a parallel to the behavior of ‘frontier model’ company OpenAI today. Their blatant strategy to fight out copyright violations with creative professionals and content creators in the court room (even supporting other ChatGPT users copyright lawsuits), their public ask for regulation to politicians while silently lobbying against it, their abysmal treatment of workers labeling data and providing “human feedback for machine learning”, and their secrecy about the steep energy and environmental costs of the gigantic server farms, are all signs that the company does not care an inch about the harmful impacts of their operations. Not only will “testing” frontier models not do anything for real safety, we also shouldn’t be surprised if companies like Open AI find ways to test and retest their models for current day digital pathogens, like misinformation or hate speech, and develop strategies to prevent anything from hitting their bottom line. It is a common playbook in the (tech) industry.

“As long as proven safety practices are not adopted, any discussion about risk lacks a factual basis to determine effective policy goals and regulatory actions, or have any meaningful debate about these.” — Dr Roel Dobbe, Delft University of Technology

Path forward

The field of system safety, matured for software-based automation in nuclear energy or aviation, provides readily available lessons and methods that should be a baseline for diagnosing and addressing harms in AI-enabled processes, both from existing and emerging safety risks. Using these will show where AI capabilities cause unacceptable risks, whether models are large or small. As long as proven safety practices are not adopted, any discussion about risk lacks a factual basis to determine effective policy goals and regulatory actions, or have any meaningful debate about these.

On Sunak’s exclusive guest list many important voices needed to gauge the risks of AI were missing, including groups already bearing the brunt of extractive and harmful systems. A more inclusive approach is needed to identify and negotiate acceptable safety risks. It is also possible, evidenced by the growing engagement across civil society and oversight bodies, many of whom gathered last week at fringe events. The next summit in Korea could correct course and steer the discussion towards the actual risks and harms that AI systems produce or which may emerge based on realistic ground assumptions, by first bringing these voices around the table.

More results /

Je medisch dossier inladen in nieuwe functie ChatGPT? Denk 10.000 keer na

Je medisch dossier inladen in nieuwe functie ChatGPT? Denk 10.000 keer na

By Natali Helberger • January 19, 2026

By Roel Dobbe • November 24, 2025

By Roel Dobbe • November 12, 2025

Combatting financial crime with AI at the crossroads of the revised EU AML/CFT regime and the AI Act

Combatting financial crime with AI at the crossroads of the revised EU AML/CFT regime and the AI Act

By Magdalena Brewczyńska • January 16, 2026

By Sabrina Kutscher • July 02, 2025

By Natali Helberger • March 06, 2025

By Maurits Kaptein • June 06, 2025

By Leonie Westerbeek • November 22, 2024

By Agustin Ferrari Braun • January 29, 2026

By Fabio Votta • November 05, 2025